Just Call Me Rudy

I wouldn’t go straight to disaster.

I wouldn’t go straight to disaster.

Actually… Nope. I would. I would pretty much go straight to disaster.

I knew I was in trouble the moment I walked through the doors of the Harry Gladstein Fieldhouse. “Umm… Why are the Alabama Crimson Tide here?” I asked Lisa as we made our way through a sea of athletes, each branded with the sharp logo of the big dogs in college athletics: Alabama, [The] Ohio State University, Arkansas, Louisville, Indiana, Notre Dame. I wasn’t prepared for this. I don’t know what I was prepared for, but it certainly wasn’t the Buckeyes.

Less than a week before, my fellow Runna Babez teammate invited me to go with her to the meet.

“Hey, Amy, wanna run in one of the biggest, most competitive collegiate indoor track meets in the nation? You’ll compete against Division I athletes at the top of their games! You’ll compete against runners trying to qualify for nationals! You’ll race against kids who’ve been running track since grade school! You’ll toe the line with girls who can run much faster than you ever will!”

Except, that’s not what Lisa said. It’s what Lisa should have said, but it’s not what Lisa actually said. Instead, she threw down this beauty:

“Wanna go with me to an indoor track meet? It’ll be fun! You can PR!”

“Okay!”

And that, my friends, is how bad things happen.

If anyone ever tries to tell you that track and road racing are the same because they’re both “just running,” you have my permission to punch that person in the Achilles. To say I was underprepared for the uber-aggressive track mentality is a gross understatement. Don’t get me wrong: I knew that racing on a track would be different than racing on the roads. I knew that the “Women’s Open 5000” would be a completely different animal than a local 5K. But I didn’t know just how different it would be. As Coach Cary commented after the race, it wasn’t that running track was new to me. It was utterly and completely foreign. Road racing and track are absolutely, unequivocally separate sports. Period. The track and the road are not sisters. They are not distant cousins. They aren’t even friends. The track and the road are more like rival countries in the United Nations: They don’t really want to be associated with one another, but every now and then their ambassadors are forced to smile and wave for a picture.

No fish has ever been more out of water than I was last weekend. I was as out of place as Shaq in the petite section. Al Gore at a coal mining convention. Miley Cyrus in pants. I mean, at one point, I was standing next to a guy who ran the 800 in 1:51 (remember, this is on a 200-meter track that’s all turns). “Hi!” I wanted to say. “My name is Amy and you look really fast and I raced the Chesterfield Turkey Trot back in November.” But I didn’t say that because he didn’t strike me as a turkey trot kinda guy.

“Wait a second… I thought I was running in an open event,” I said as the details about the nature of the whole affair began to surface.

“You are,” Lisa said.

“Open like, ‘Anyone can run.’”

“No, you had to qualify for this.”

“I had to qualify?”

“Yes.”

“But I thought it was open to anyone who wants to run. Hence the term, ‘open.’”

“Amy, it’s ‘open’ like the U.S. Open. Just because the U.S. Open has the word ‘open’ in it doesn’t mean that anyone can grab a tennis racket and start playing.”

“Oh, yeah. I forgot about that kind of open.”

Guys, let me put this in perspective for you. The first race I ever raced was a marathon. Not a 5K. Not a half. But a full marathon. I was twenty-four. In fact, until 2007, I had never even stepped foot on a track. Sure, I’ve raced before. But I’ve never before raced other people. When I toe the line of a marathon, half marathon, or even a 5K, I’m racing a time. A PR. A course. Where I place in the overall standings is wholly contingent on who else shows up that day. From my running infancy, I have trained to know my ability, to pace myself, and to run my own race. I have learned not to go out too fast. I have learned to disassociate from the world around me, lock into a pace, and go. I have learned that patience is a distance virtue.

And now I have learned that everything I know about running is wrong when you’re on a track.

In track, your watch doesn’t pace you; the lead pack does. In track, you don’t compete against time; you compete against the person next to you. In track, you don’t run your own race; you run the one that’s handed to you. In track, your goal isn’t to run a certain time; it’s to win.

These kids came to Indiana prepared to run fast. Despite their young ages, they were experienced track veterans. They weren’t just acquainted with speed and intensity; they were married to it. When the gun went off, they were ready. I was not.

The good news is I didn’t finish last. (I was second to last!) The bad news is I did it all wrong.

From the moment I crossed the threshold at the Harry Gladstein Fieldhouse, I was the proverbial deer in headlights. In fact, I’m pretty sure your average deer in headlights processes things faster than I did. I was blindsided by the intensity of the atmosphere. I was overwhelmed by the foreignness of it all. I simply didn’t know what I was doing.

I was the Denver Broncos in the Super Bowl.

Earlier that day, I had briefly rehearsed my race strategy. I knew my PR. I knew the race would be faster than that. I would try to hang with the pack, but not go out at suicide pace. Eventually, the pack would thin out, and I’d find someone to run with. That was the extent of my preparation (other than the batch of oatmeal and chocolate chip cookies I had made the day before).

And then, suddenly, I was on the track and the race official was lining us up and the gun went off and we were running.

The girls went out fast—faster than we expected. I ran the first lap with the pack, took one look at the clock, and began reeling it in. This is too quick! I thought. I need to slow down. I won’t be able to hold this pace.

In other words, it took all of 200 meters for me to make my first wrong decision.

From the second lap on, I ran by myself. All by myself. If I had been wearing a visor and a water belt I couldn’t have looked more like a road runner. A single spectator, presumably compelled by sympathy, adopted me midrace. I was bolstered by her encouragements every time I rounded the first turn.

“C’mon, sixteen!”

“You can do it, sixteen!”

“Hang in there, sixteen!”

“Keep trying, sixteen!”

“I’m sure your mom still loves you, sixteen!”

“Unless you wanna run the men’s 60-meter hurdles, you’d better get off the track, sixteen!”

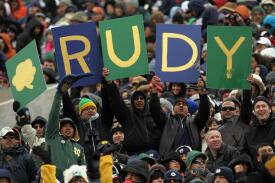

In other words, I was Rudy.

The moment of truth came halfway through the race. The girls were still running fast, and the race wasn’t breaking up. For all practical purposes, it was a two-pack race, without much separation between. If I wanted the slightest chance of catching up to the crowd, I needed to gun it, right then. I remember hearing Lisa scream, “Go, Amy! Catch that girl!” I remember her yelling something about not letting them get any further ahead. I remember thinking I had two choices: to throw caution to the wind and go for it or to run my own race at a doable pace. I remember all of this happening in a split second. And I remember making my choice.

I chose wrong. (Cue the losing horn from The Price is Right.)

In the heat of the moment, I forgot to remind myself that I wasn’t on the roads. Like a deer in headlights, I froze. I did what I’ve always done. I forgot I was playing a different sport.

I’ll be the first to admit I’m not the best at making calls at the line of scrimmage. I wasn’t graced with killer instinct. Give me a play, and I’ll own it. But if you throw me a curveball, I may or may not adjust in time. The rank of the meet, the unfamiliar territory of the track, the 200-meter circles, and even the nakedness of running without a watch threw me off what little game I had heading into the race. I tried to adjust by occasionally looking at the clock that was mounted at the start line; but even then, I didn’t realize officials would stop the clock when the first girl crossed the finish line. The result? I ran an extra lap, just to make sure I didn’t stop early.

I know. Even I feel bad for me.

I did end up passing one girl with about a half mile to go and was only a few seconds behind another before I ran out of real estate. But the worst part of the race wasn’t that I had run alone. It wasn’t that I didn’t run the PR I wanted. The worst part was that when I crossed the finish line, I wasn’t exhausted. I had played it safe—too safe—on a stage that demanded anything but.

And I’ve been beating myself up over it ever since.

Now, I know. This was a new experience for me, and I’ve been telling myself all the consolation clichés I can think of. It was baptism by fire. Live and learn. I’m stronger for the experience. All that jazz. But the athlete in me can’t help but take it hard. Sure, the Wright brothers crashed a hundred times before their first successful flight. You have to fail before you succeed. I get it. But at least the Wright brothers were the first to make an airplane that worked. Imagine if the Wright Flyer were bouncing around the tarmac at O’Hare International Airport today, with American and Delta and United rolling their eyes like, “Are these guys for real?”

Puts a different spin on the whole Orville and Wilbur story, doesn’t it?

I relived the race for four and a half hours during the car ride home. And all that night. And the next day. And the next. I’ve tormented myself with a hundred “If onlys…” I know I could have hung for a little while. I know I could have raced better. I know I could have run faster.

If only.

I talked to Coach Cary after the race. “You did what you knew how to do,” he said. “When you’re nervous or fatigued, you do what you’ve always done. You fall back on what you know.” He shrugged. “Road racing is what you know. But what you learn on the track is going to help you on the roads. And you learned.” He smiled. “Plus, who’s going to intimidate you now? You just lined up with a bunch of Division I athletes.”

Am I disappointed in myself? Absolutely. Am I mad? Yeah, a little. Okay, a lot. But I’m glad I raced. I was baptized into the world of track. I learned a new definition of what it means to race. I was reminded that a current PR and potential aren’t always synonymous and that pace does not necessarily equate ability.

I was reminded that numbers alone do not a race make.

One last note: How much of a road runner am I? Don’t tell Lisa, but just over half way through the race, I did the most road runner thing of all.

“Good pace!” I said as the lead girl passed me. “Looking strong! Keep going!” I realized my mistake the moment the words left my mouth. (And from the “What the…?” look she gave me.) Oh, man! I thought. You’re not supposed to do that in track…

Ah, well. You know what they say. Live and learn.

Amy L. Marxkors is the author of The Lola Papers: Marathons, Misadventures, and How I Became a Serious Runner. Her second book, Powered By Hope: The Teri Griege Story, will be released in 2014.

Connect With Us

see the latest from Fleet Feet St. Louis