"Talk to me, Goose."

I was on the treadmill. For reasons I can’t for the life of me remember, I decided to knock out my eleven-mile run in the basement accompanied by the cheery milieu of a vestal Total Gym and a Cuisinart box boasting not only the original Cuisinart, but also a stockpile of old receipts and a vagabond Sharper Image catalog.

I was on the treadmill. For reasons I can’t for the life of me remember, I decided to knock out my eleven-mile run in the basement accompanied by the cheery milieu of a vestal Total Gym and a Cuisinart box boasting not only the original Cuisinart, but also a stockpile of old receipts and a vagabond Sharper Image catalog.

“We’re in his jet wash… This is not good!”

[insert chaotic dogfight scene]

“Engine one is out... and your two is out!”

“Goose, I’m losing control! I’m losing control! I can’t… I can’t control it!”

“Mayday, mayday. Mav’s in trouble. He’s in a flat spin heading out to sea!”

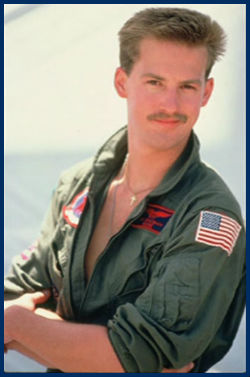

I was watching Top Gun on a 19-inch box television, a primeval TV/VCR combo that sat on a demoted bedside table and weighed the same as a small rhinoceros. I was maybe eight miles into the run. Maybe.

“Goose! I can’t reach the ejection handle… You’re gonna have to punch us out! Eject!”

“I’m trying! I’m trying!”

“Eject! Eject! Watch the canopy!”

And then Goose dies.

Now, in case you have not seen Top Gun (as if that were possible!), no, I did not just spoil the end of the movie. Firstly, Goose doesn’t die at the end of the movie. He dies more towards the middle. Secondly, everybody knows that Goose dies. Goose always dies. I’ve seen Top Gun approximately 1,528 times, and every single time, Goose dies.

Still, even though I knew it was coming, I was sobbing before the third note of the “Goose is dead” song. Sobbing.

Running while crying is perhaps one of the most uncomfortable activities in the world. It is tremendously uncomfortable. Your throat tightens and starts to burn. Your eyes fill with salty tears and start to burn. Your chest becomes confused by the dual muscle spasms of trying to breathe because you’re running and trying to breathe because you’re crying and finally joins your throat and eyes in burning simply because it doesn’t know what else to do. Your muscles, feeling left out, start to burn as well. Before you know it, you are a veritable anatomical inferno. Yes, running while crying is an either-or decision. You can cry or you can run, but you can’t do both. Namely because you can’t breathe when you try to do both.

When did I become such a softy? I wondered as I plopped my feet on either side of the treadmill and straddled the whirling conveyor belt.

Well, I believe I became a softy the moment I crossed the finish line of my first marathon. Ironically, I didn’t cry. There was no emotional epiphany. The race wasn’t a tribute to a loved one or the victorious culmination of a personal struggle or tagged with any other kind of higher purpose that would have occasioned an understandably emotive response. I was there simply because a friend had tricked me into training with her and then guilted me into running the actual race.

Nevertheless, something had happened over the course of four months as we chalked off twenty-mile long runs and woke up hours before sunrise and stood guard while the other used the “bathroom” (a.k.a giant rock). Something happened when we slapped high fives after good runs and stopped to walk during bad ones and talked about what we were going to eat regardless.

My heart was being softened.

It’s a wondrous phenomenon, one that is contrary to reason, but the more I run, the more I train myself to push the pace and endure discomfort and deny my body’s desire to quit—the more I am able to ignore pain—the more pain I actually feel. No, not my own. But that of others.

You see, runners are a passionate group. We have to be. The entire sport of distance running is counter-intuitive. And uncomfortable. And inconvenient. (“Hey, I have a great idea! Let’s run for hours and hours as fast as we can! Preferably before dawn!”) Heck, our sport was invented by an ancient Greek courier who ran over twenty-five miles from Marathon to Athens to announce victory over the Persians and, upon delivering his message (“Joy to you! We’ve won!”), collapsed and died.

Granted, he had run like 140 miles the day before, but whatever.

Distance running was birthed from passion. It is a religion of resolve that tests the faithfulness of both mind and body, and its adherents must practice a daily litany of commitment, tenacity, and self-discipline. We get sick, tired, hungry, injured, defeated, and broken—and we run anyway. We run come rain, come snow, come sleet, come hail, come hell or high water (and sometimes both). We train our bodies to accept pain, endure pain, ignore pain, and respond to pain with a gritty, “Suck it up, buttercup.”

Yes, we are tough. We are strong. We are gristly. But we are not hard-hearted.

In order to run—really run—you have to care. A lot. Distance running is a lot of things, but it is not apathetic. For all the craziness and quirkiness in the sport, there is just as much trial and struggle. For all the joy and companionship, the miles can also be very lonely. For every victory, there is a defeat. For every hammered run, there is a wall. The marathon can take us to euphoric heights. It can also drive us to places of great darkness. We are forced to reach deep within ourselves. We are exposed. We are raw. We are real. A runner is nothing if not very, very human.

Robert Frost wrote of the softening agents of human experience:

I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain—and back in rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain…

Runners have been acquainted with the night. Yes, our hearts are strong. But there is a difference between strong and hard. Every hard workout, every blown race, every mile of disappointment, fatigue, loneliness, and defeat softens our hearts even as it fortifies them. We see others’ pain, and instead of feeling less, we feel more, because we’ve been there. We know the pain of loss, the finality of a blown opportunity, the difficulty of persevering through fatigue, and the frustration of ongoing struggle.

Someone once described compassion as crawling into another person’s skin and figuring out what needs to be done to bring comfort or to fix the problem (or both). I think that’s why, in many ways, the endurance sport community is a community of compassion. We cry out cheers of encouragement to fellow runners in passing. We speak soft words of reassurance to friends struggling through the final miles of a race. We hold signs and ring cowbells and stand for hours in the freezing rain just so we can see them for a split second, just so they know we are there, just so we can wave and yell a quick “Keep going! Lookin’ good!” even as the sound of our voices fades with their every step. Because we get it. We feel it deeply. As King Solomon said, “A man has joy by the answer of his mouth, and a word spoken in due season, how good it is!”

Carefully, I hopped back on the whirling conveyor belt and clomped through the final miles of my run. I figured if Maverick had reengaged, I may as well, too. Plus, it wasn’t all doom and gloom over the Indian Ocean. Maverick and Iceman finally became friends, Merlin got a few extra lines of script, and Goose went on to have a very successful career as a fictional surgeon on ER.

I was still singing “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling” (whoa-oh-oh) as I grabbed my water bottle, flipped off the TV, and headed upstairs.

I can’t believe I just cried during Top Gun… Seriously. When did I become such a softy?

Well, I guess you could say I became a softy the moment I became a runner.

Amy L. Marxkors is the author of The Lola Papers: Marathons, Misadventures, and How I Became a Serious Runner. Her second book, Powered By Hope: The Teri Griege Story, will be released in 2014.

Connect With Us

see the latest from Fleet Feet St. Louis