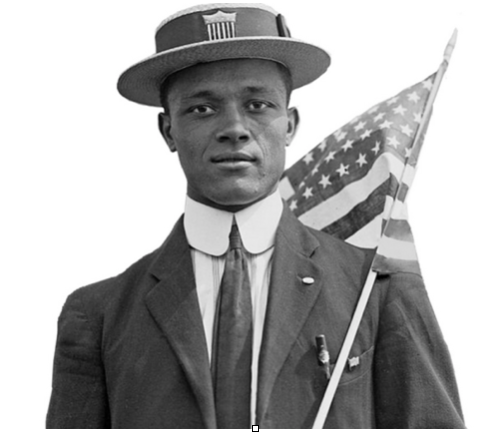

Harold Drew (1890-1957) was a 1912 Olympian, AAU champion sprinter, world record holder, WWI veteran, lawyer, judge – and probably the first person described as “the fastest man in the world.”

Harold Drew was born in Lexington, Virginia in 1890, but his family, like so many African-Americans in the early 20th century, chose to join the Great Migration to northern states to avoid raising their children in the Jim Crow South. Therefore, young Harold grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father, a Baptist minister, strongly encouraged Harold to pursue excellence in all things, including athletics.

Drew often did not have suitable sports equipment but he won anyhow. Necessity being the mother of invention, he took on the challenge of creating his own sportswear, fabricating a more durable type of running shorts and even making an early version of spikes by inserting roofing nails through the soles of his tennis shoes and using leather as a sock liner to cover the nail heads. He described running in these shoes as “walking on a sea of glass mingled with fire.” While he won the 1905 Springfield City Games 100-yard race wearing them, they were so excruciating that he chose to run the day’s next race – a 440-yard race on a cinder track – barefoot. He won that one as well.

However, like many African-American students of his era, Drew’s family responsibilities interrupted his education. He had to drop out of high school during his freshman year (1906) to help support his family. When he returned to Springfield Central in 1910 to finish his high school education, he was a 20-year-old man who was hungry to compete.

Harold became a multi-sport athlete – football running back (3 years), baseball left fielder (4 years), and track sprinter (4 years). His record-smashing performance for Springfield Central High School’s track team in the sprint events brought him to national attention. During his sophomore year, he posted world-class times and personally outscored the collective efforts of opposing teams. By his junior year, he was the captain –– a highly unusual honor for an African-American athlete at that time — indicating how highly he was valued by his team and his school.

While he and his family were well-respected in Springfield, he and other African-American athletes were regularly demeaned in the region and nation. Drew resolutely insisted on his human dignity, turning down opportunities to compete at Boston AAU events because he would not allow his celebrity to be used to make money for an organization that would not allow African-Americans to represent them. A proponent of “racial uplift,” Drew chose to use his athletic prowess in ways that would promote African-American accomplishment in the classroom.

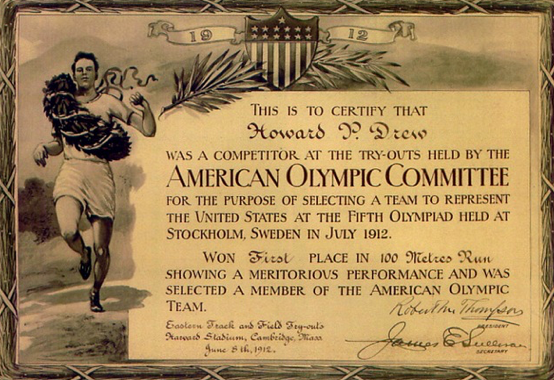

In 1912, while still finishing high school, he set his sights on the Olympic Games. His impressive string of wins included the Harvard Stadium Olympic Qualifier and the US Trials, where he easily beat the field pulling away.

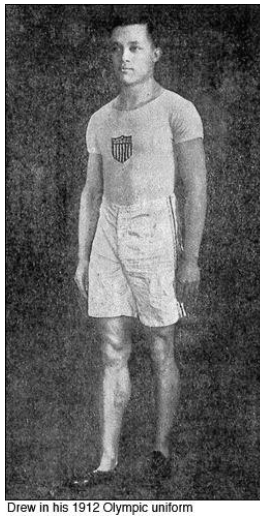

He competed at the 1912 Stockholm Games, qualifying for the finals in both the 100m and 200m races. He was the presumptive favorite to win, but while on his way to placing first in the 100m semi-final heat, he pulled his hamstring as he stepped on a soft spot in the track. He could only watch as the man he had repeatedly beat in the heats – US runner Ralph Craig – cruised to victory.

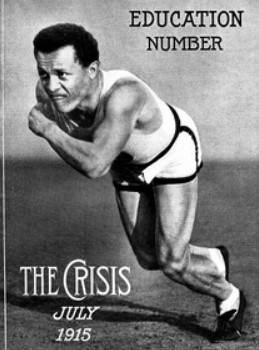

Eager to run at the collegiate level, Drew then headed to the University of Southern California (1913-1916). He paid his way through school on a work-study program; he also made extra money as a journalist, writing regularly for the Los Angeles Examiner and as a sportswriter for the USC school paper. On the track, he showed no signs of slowing down, tying or setting world records in most of the short distance events and becoming AAU National Champion for 100 and 200 yd distances. His 1914 world record in the 100m dash (9.6 seconds) stood until 1929.

He graduated with honors and moved on to study law at Drake University and coach their track team in 1916-1917.

Drew hoped to compete in the 1916 Olympics, but international events intervened when World War I started and the Games were cancelled. Drew remained in peak physical condition, however, as he exhibited at the 1916 Millrose Games. At a special invitational event that brought together four of the world’s fastest sprinters for a high-profile showdown at 70 yards, Drew ran down the field and equaled his own world record time (7.15 seconds).

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Drew enlisted in the US Army (88th Division, 809th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, Supply Company) and won both a Victory Medal and a defensive bar during his service in France.

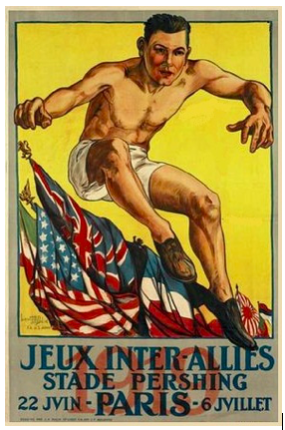

Rapidly promoted to First Sergeant, Drew also took on the important job of coaching US Army track teams for the so-called 1919 “Pershing Olympics.” The international media eagerly promoted his return to competitive running, but there is no record of him taking part as anything but a coach and trainer. He was honorably discharged in 1919.

While Drew still hoped to make the Olympics in 1920, he was 30 years old and other younger men outran him. Perhaps his mind was on his studies, because only a few months later, he passed the bar exam in Connecticut, becoming one of the few African-American attorneys in the state. His legal practice in Hartford, Connecticut, steadily grew; using the same focus on excellence he had cultivated as a scholar-athlete, he became the first Black judge in Connecticut. After a long and distinguished career in public service, he died in 1957.

(With thanks to Dr. Bridgett Williams-Searle)

Connect With Us

see the latest from Fleet Feet Albany & Malta